Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Thank you for signing up to . You will receive a verification email shortly.

There was a problem. Please refresh the page and try again.

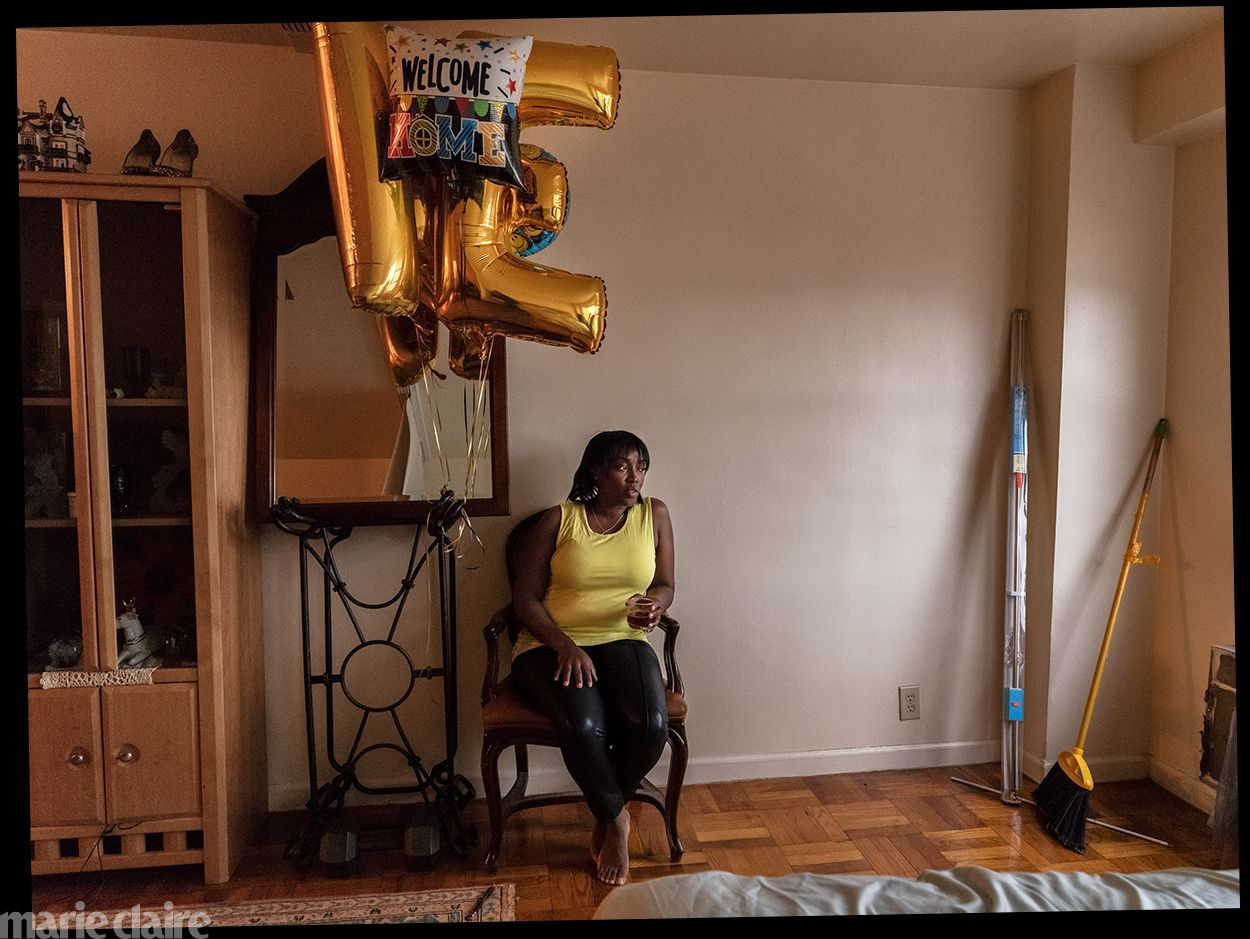

On the morning Makeda Davis was coming home, her mom, Georgia Davis, cleaned her studio apartment, smoothing a tablecloth over a table and putting out bowls of Doritos and pistachios and a Welcome Home balloon. Makeda’s daughter, Merhanda Pierre, had bought a charm bracelet featuring a heart engraved with the word Free. Later, as the two women pull into the parking lot of Bedford Hills Correctional Facility in Bedford Hills, New York, they buzz with energy: After seven and a half years in prison, Makeda is getting out for good.

Behind barbed wire, the prison grounds (green grass, brick buildings) look dull and still on this rainy November day in 2018. Merhanda, 21, tumbles out of the car, batting at unruly gold K and E balloons (for her mom’s nickname, Ke). Georgia, age 59, clutches her purse, a bit more hesitant. That morning, Georgia looked around her small home, describing how “everything fell apart” after Makeda went to prison. Before, they lived in a much bigger place thanks to Makeda’s salary. “She was the heart of the family,” she said. “Now, it’s like she’s coming back to put the pieces back together.” She paused, then added softly, “Maybe not.”

Makeda Davis on the day of her release from Bedford Hills Correctional Facility in November 2018.

Then, a door of the trailer where visitors are admitted—and where, every once in a while, inmates are discharged—opens. It’s Makeda: brown skin, black hair, wide brown eyes, a giant smile. As she walks down the trailer steps, wearing a rain poncho and holding a plastic bag—all she’s taking with her from this place—Merhanda and Georgia run toward her as though pulled by magnets. They move together, Georgia crying and saying, “My heart burst” as she hugs her daughter and pulls the hood of the poncho over her head. Merhanda wipes her mom’s nose. “Hug me, Mama,” she says, and the three women meld closer.

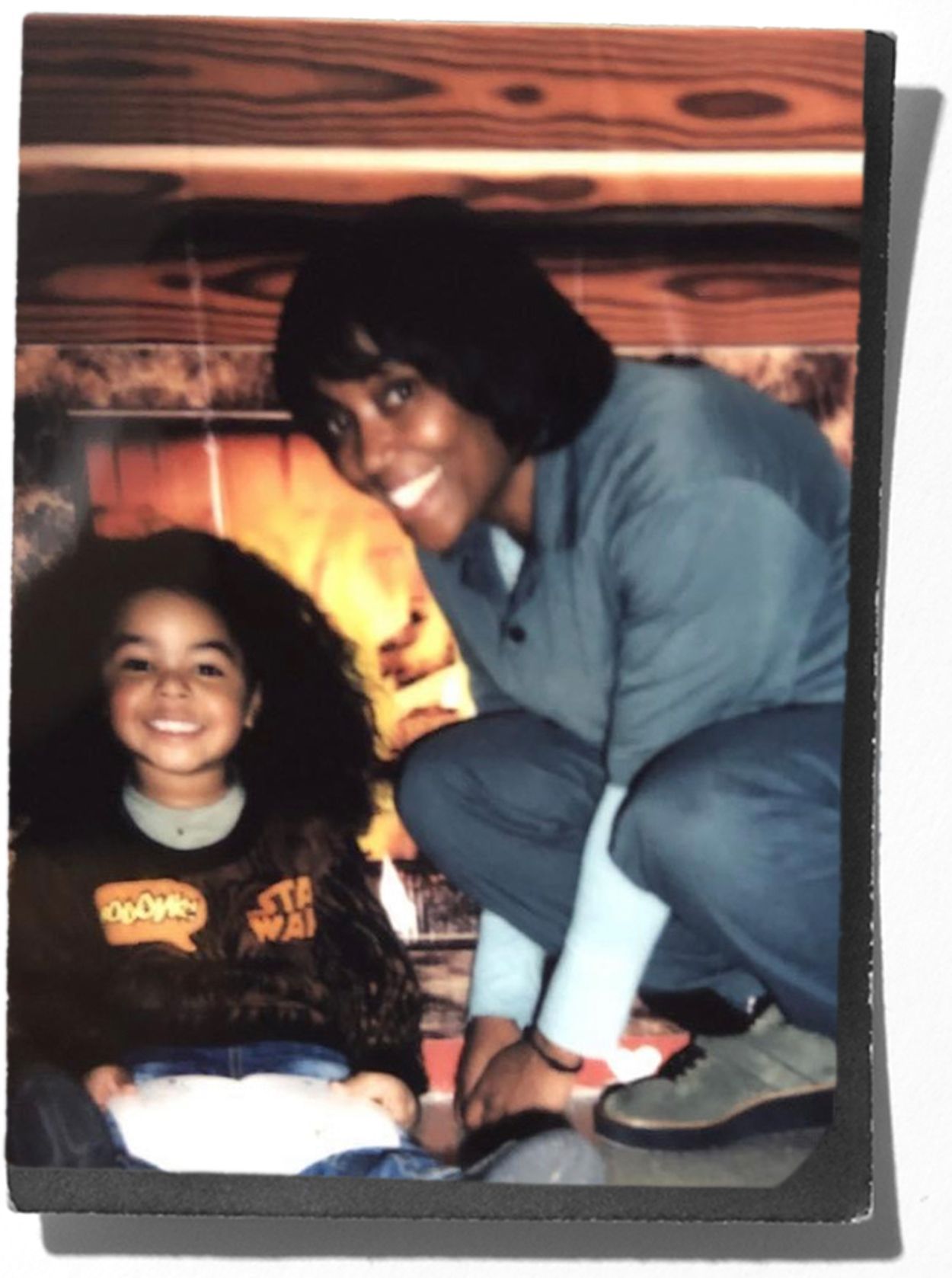

Makeda and daughter Merhanda Pierre in 1998.

Makeda, as much as she’s been waiting for this moment, doesn’t know quite what to expect. She was convicted of assault after a 2006 nightclub fight. When she went into prison, her daughter was a kid; now she is an adult living on her own. “I don’t know what life is going to be like after all these years,” Makeda mused a few weeks earlier, sitting inside the prison library at Bedford. She ticked off outside-the-walls things she didn’t understand: Uber, streaming TV, avatars, online banking. “Things are changing so fast—and where do I fit in?”

The first year out of prison is critical for ex-inmates. They’re often leaving prison with little money, uncertain housing, fractured relationships with family, and no job, not to mention the psychological toll of incarceration. “They’ve got to construct a whole life for themselves: Where am I going to live? How am I going to have money in my pocket to eat, clothe myself, get across town?” says Ann Jacobs, executive director of the Institute for Justice and Opportunity at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Makeda has some sense of how hard this next year will be—but there’s also a lot she’s looking forward to: eating Jamaican oxtail, fresh vegetables, and sushi; decorating for Christmas; a big 40th birthday party. More than that, though, she wants her career back. Before she went to Bedford, she had a good job as a legal assistant for the city of New York. “I think of my daughter; she’s so beautiful, and she has all these expectations. I’m gonna be so hurt if I’m a mom that can’t be there for her child,” she said just before her release. Her eyes reddened. “I have things that I want to do in my life; where I start, I’m not exactly sure.”

Makeda and Merhanda reconnect at Georgia’s apartment in Queens, New York. Makeda hadn’t worn a tank top in years; it wasn’t part of her prison uniform.

For now, it’s about getting Makeda out of the rain. Her mom and daughter walk her to the back of the SUV’s open trunk, and she sits between them, a little dazed. Merhanda, tall and curvy with intricate makeup and long braids, combs her mom’s hair while Georgia, petite in a sweater, slacks, and glasses, fixes her bangs. Between them sits Makeda, smiling so wide, her teeth don’t touch. Merhanda snaps a selfie and shows her mom, who stares at it. “I didn’t know that was me,” she says.

“That is you, girl,” Merhanda replies.

Merhanda puts on a Drake song, singing, “Kiki, do you love me?” As Makeda gets into the car, she says she’s been crying for the last three days. This morning, seeing for the first time that trailer where her family had to check in for visits nearly put her over the edge. “I thought it was all clean and nice. I was like, I can’t believe my mother had to come up here all these years to this dirty little...” She trails off. “It’s not okay.”

The car heads for Queens, New York, where Georgia lives, and Makeda flicks through cell-phone photos of what she’s missed. At the apartment, she examines everything, picking lids off of pots and opening cupboards, then changes into a tank top. “I haven’t worn a tank top in so long,” she says; in prison, she mostly just had to wear Bedford’s forest-green pants-and-shirt uniform. “It feels like I’m breaking a rule.”

Yes, Makeda is home, but she has a mom and a daughter to help support, housing to find, food and medical bills to pay, a job to look for. All the responsibilities of middle age with none of the stability.

“Where should I go? Where should I begin?” she asks, not directing the question at anyone.

Makeda’s life plan did not, needless to say, include prison. She hoped, instead, to get away from the instability and violence that started for her in second grade, when her father was shot and killed while taking her younger brother to the park; she still doesn’t know why. Makeda stepped up after that, handling schedules for her two brothers and then getting work bagging groceries and shampooing hair at a salon.

Her family moved around New York City as Georgia looked for better housing and jobs and safer neighborhoods. At 17, Makeda had her daughter. Though she didn’t finish high school, she got her GED. Makeda worked as a legal assistant and was taking online college courses when she got into the nightclub fight. She and the victim were arguing over a man, and Makeda says the two started brawling, a lot of other people joining in. “It’s just really sad,” she says of the fight. After Makeda’s 2008 trial, where the prosecutor showed photos of the victim’s initial wounds and the victim accused her of carrying something sharp like a razor—a point Makeda denies—she was convicted and sentenced to nine and a half years in prison.

“In our communities, people getting in fights, you don’t think the consequences would be so extreme,” she says. “You watch Madea, and she’s talking about throwing grits on people. No one’s gonna tell you, ‘You throw grits on your boyfriend, you’re going to be doing [time].’”

After less than a year behind bars, Makeda was released on bail pending an appeal. Her attorney was appealing her conviction on the grounds that the prosecutor had erred in the grand-jury presentation. When the New York Appellate Division initially reversed her conviction, Makeda thought she was free. She pieced her life back together, firming up her relationship with her daughter and mother, getting a job as a staffing coordinator at a long-term care facility, and finding a roomy top-floor apartment in Rosedale, Queens, that the three of them lived in. “Finally, when I thought that everything was fine, I learned I had to go back to prison,” she says.

In early 2012, after another reversal by the Court of Appeals, the Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court upheld her original conviction for assault in the first degree. She had to return to Bedford, an hour north of Manhattan, where she’d stay for almost seven years. “I’m like, I’m not gonna make it through this time,” she says of her mental state during those first months back. While she rejoined the college program she had started during her first prison stint, she mostly stayed close to where she slept, in a dormitory with a metal bed frame and locker, refusing to talk to people, declining invites for card or domino games. That went on for more than two years, until she had terrible cramps from endometriosis and another inmate noticed and made her fresh ginger tea. The act of kindness led Makeda to socialize more. Eventually, she earned her associate’s degree from Marymount Manhattan College, a New York college that runs a program at Bedford. She also worked for a program called Hour Children, which, at Bedford, runs a nursery and children’s center, along with arranging visits between incarcerated mothers and their kids.

Other than those activities, though, Makeda’s life in prison was largely a combination of boredom and pointless protocols: waiting an hour at the medical clinic for a scheduled appointment and then waiting for a guard to walk her back to the library.

Over the years, she saved $300, earning 50 cents an hour answering phones for New York’s Department of Motor Vehicles and 22 cents an hour working at the Hour Children program. Though Bedford is considered by many criminal-justice experts to be a fairly progressive prison (the superintendent allows outside groups to run programs there), Makeda questions the point of her being locked up.

“It starts to feel like you’re on a plantation,” she said during her last weeks in prison. “Most people are going back into society, so why create an atmosphere where the people are leaving here worse than they came in?”

A couple of weeks after she leaves Bedford, Makeda walks into the lobby of the Fortune Society, a Queens-based nonprofit that helps people who were incarcerated transition back to regular life. As clients stream by the reception desk for classes or appointments, Makeda sinks into a chair.

Things aren’t going great. She’s out of money, borrowing from friends, and she just found out she didn’t get a job she applied for online. She’s been at it with Merhanda, who quit her jewelry-store job just after Makeda came home. Merhanda, who lives with roommates, seems to want all of her mom’s time. Makeda has been drowning in logistics like gathering the required paperwork for food stamps and obeying her parole restrictions. And she and her mom, who were so close when she was in prison, now seem like mismatched Craigslist roommates, squabbling over Wi-Fi, bedtime, and what TV show to watch.

When she’s first out of prison, Makeda sleeps on a mattress on the floor of her mother’s Queens apartment. “Where you rest your head has a tremendous effect on how you feel,” she says.

When doing everyday things like grocery shopping, Makeda says, she feels slow and awkward, trying to remember what juice brand she used to drink and learning what new products came out while she was away. Her pants barely fit. (Thyroid issues developed in prison and, along with unhealthy prison food, caused her to gain weight.) The subway freaks her out: Seeing so many men is unnerving after years of living with only women.

“I feel so overwhelmed and messed up on so many different levels,” she says.

James Judd, Fortune’s supervisor for the admissions unit, calls her into his office. Today, Makeda hopes to get a parole requirement that she take weeks of drug-counseling classes waived, as she’s never used drugs. In some cases a parole officer can allow a counselor to decide whether or not someone actually needs substance-abuse treatment.

“Were you incarcerated?” she asks Judd.

“Eight years,” he says.

“Get outta town. God bless you,” she says.

Her phone rings. Merhanda. “When she calls, if I don’t answer, she’ll have, like, a heart attack: ‘You’re ignoring me!’” Makeda picks up, reminding her daughter to take her vitamins.

Judd asks about Makeda’s primary source of income. None; just food stamps, she answers. She’s ashamed about this; she can’t remember if she needed them even when she was a teen mom.

He tells her what Fortune offers: help applying for public assistance and the benefits to which she is entitled, such as food stamps or health insurance, access to lawyers, job-placement services, and parole-required programs, along with free hot meals for clients.

“Why’d you ask if I did time?” Judd wonders.

“It’s motivational to me,” she says. “Like, I can do this.”

Without formal mentorship, Makeda is grasping for guidance everywhere. She recently attended a church-basement meeting of people who were formerly incarcerated, but there her old idea of herself as a with-it professional crashed against the reality of these people, mostly men, many of whom had done long stints in prison and were now her peers. “What have I done to my life?” she asks. “I feel so ugly, and I feel so old and out of whack and broke and broken—all these feelings that I really didn’t expect to feel.”

After getting the drug-counseling requirement waived, Makeda picks at carrots and a burger in Fortune’s cafeteria. “I feel like if you’ve done your time, you should be able to live your life,” she says. “I just want things to move faster.”

The deck is stacked against people getting out of prison. American prisons were mostly formed about 200 years ago, and women’s prisons opened up about a century later. Around the time Bedford was founded in 1901, prisons had progressive goals of improving their inmates. Those benchmarks largely disappeared as funding shrank, reform-minded superintendents moved on, and overcrowding and logistical issues (such as handling mentally ill, sick, and violent inmates) took over.

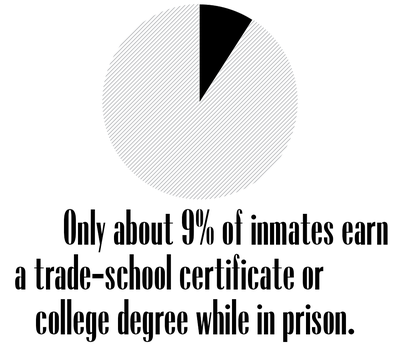

Today, most prisons tend to run limited programs on anger management or drug addiction, along with some job training; only about 9 percent of inmates earn a trade-school certificate or college degree while in prison, and a minority of prisons run college programs, according to the Vera Institute of Justice. That means inmates’ situations don’t usually improve—and that reality is stark when it’s time for them to leave.

Even before their incarceration, inmates make far less money than their counterparts who don’t do time; experts say that is because people, especially people of color, from poor communities tend to be more heavily policed and prosecuted. That’s only exacerbated by time in prison, where inmates often make far below a dollar per hour for work and pay high fees for things like phone calls. If someone goes to prison, that person’s family will likely incur increased childcare costs as fallout—among other effects.

Many prisons have plans for reentry, according to Chidi Umez, a project manager at the Council of State Governments Justice Center, which advises state officials on criminal-justice issues. “If a prison doesn’t provide a reentry plan, it’s pretty much [that] you get out, and you get dropped off at the bus station, and you get a bus-fare card, and you’re left on your own to figure it out,” she says.

Prison has few of the rhythms of regular life, and it’s hard to get a job when you have a resume gap and few up-to-date skills. Also, there are some 45,000 federal and state statutes and regulations that can affect a convicted person’s ability to get and stay on his or her feet, an American Bar Association project found, ranging from not always qualifying for food stamps to being prohibited from working or volunteering with children.

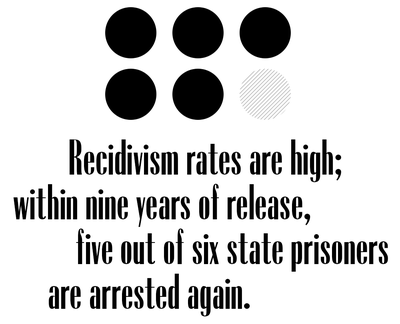

A swath of nonprofit, state, and local programs aim to solve these issues, offering resources like housing, food, or employment training. They often have limited funding, though, so they can cover only a small number of people, and even something simple like letting prisoners know the groups exist is tough, as individual prisons tend to have their own protocols for reentry. With about 10,000 prisoners going home every week in the U.S., many are left without an obvious path forward. Recidivism rates are high; within nine years of release, five out of six state prisoners are arrested again, according to government statistics.

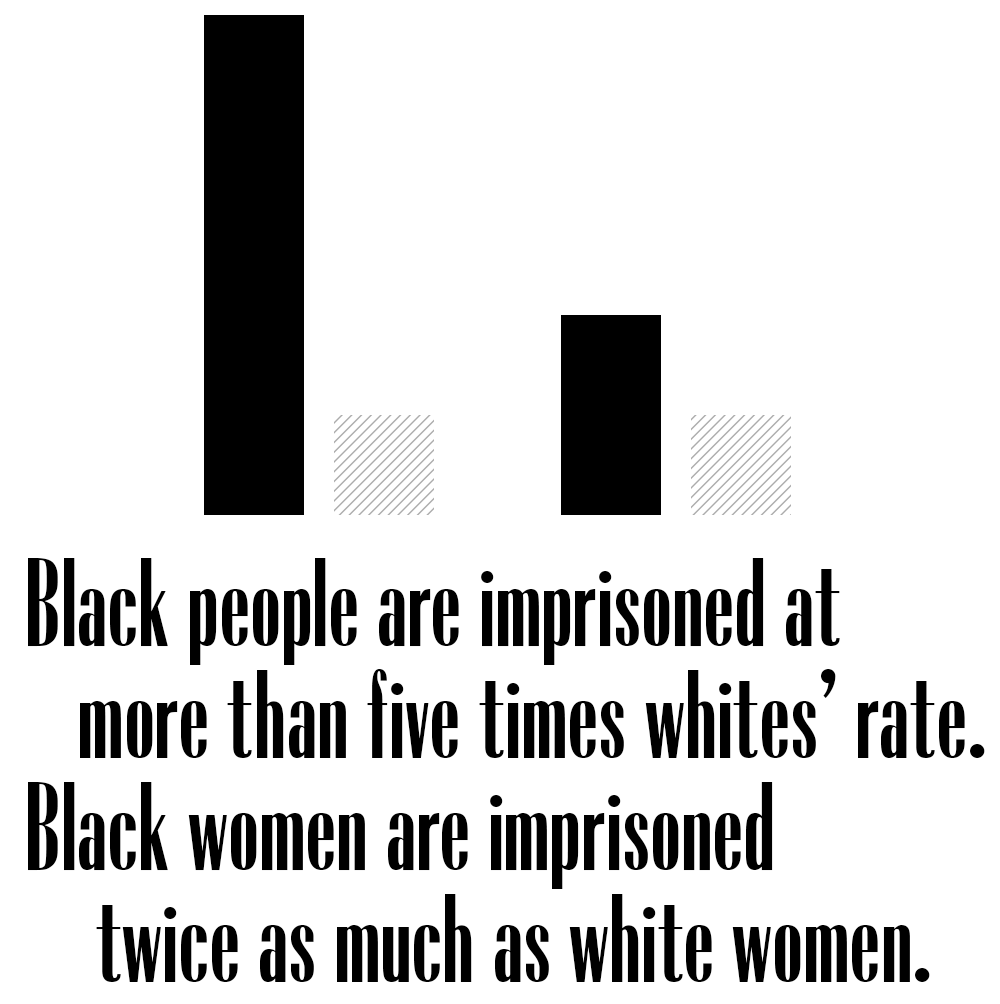

When Bruce Western, a Columbia sociology professor and codirector of its Justice Lab, conducted a yearlong study of about 120 people leaving Massachusetts state prisons, he found that even before incarceration, the defendants had rocky lives. Most grew up poor and exposed to violence. Afterward, most slid into severe poverty, especially the African Americans, underlining “the unusual disadvantage of African Americans at the nexus of the penal system and the labor market,” Western wrote. Indeed, people of color are disproportionately imprisoned: Hispanic people are sent to prison at three times the rate of whites, while black people are imprisoned at more than five times whites’ rate. Black women are imprisoned twice as much as white women.

“It’s one of the great paradoxes of incarceration: People are being punished very harshly, and it’s difficult to draw a clear line between the criminals offending and their vulnerability and victimization,” Western says. “People are dealing with social contexts that are very, very challenging. What we should be thinking about, instead of trying to reduce recidivism, is trying to find a secure and safe place for people in their communities and families after incarceration.”

It’s a cold March night, and students practically sprint into Marymount Manhattan College’s big brick building on the Upper East Side. Makeda, four months out of prison, comes straight from her new full-time job handling human resources for a home-health-care agency, just in time for class. She qualified for a scholarship and recently started night classes toward her bachelor’s degree.

Dressed in her work clothes, Makeda sits next to decades-younger students in Converse sneakers and sweats. It’s a criminal-justice class, and at first, none of the students knew she’d been in prison. It “gave me a lot of anxiety” to join the class, she says afterward over pasta; she worried parents of the students might force them to boycott the class if they knew of her history.

As she noticed how little exposure other students had to the criminal-justice system, though, she spoke up. “In order for you to open up the minds of people, you have to be speaking from the inside,” she says. “I have a responsibility to teach my way. And my way is not to say every criminal is innocent, or every criminal is right, but every criminal is a human being.”

Today, she jumps into a discussion about the case of Empire actor Jussie Smollett. Her questions are incisive and informed: Will he have to pay restitution? Why were his charges originally dropped?

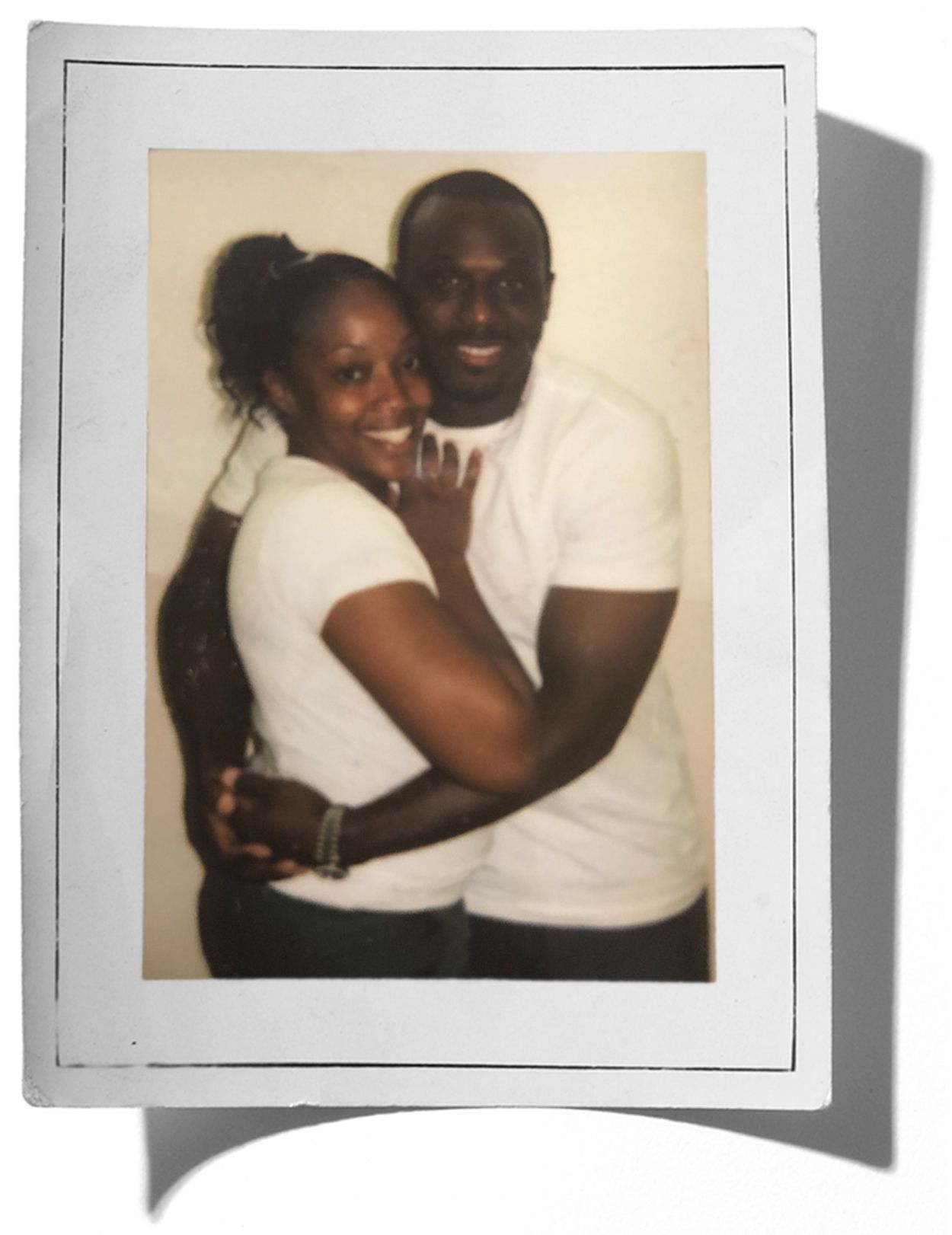

Makeda with her boyfriend Erik in 2008; he stood by her during her time in prison.

After class, she reflects on her months at home. A lot that she wanted hasn’t come through. No Christmas-tree decorating; the family didn’t seem to have money or energy for it. No 40th birthday party; she didn’t feel like celebrating. The boyfriend she’d been with prior to prison, who she thought she’d be with again, was seeing someone else. Her job pays close to minimum wage, and, though New York prohibits employers from denying employment to those with records in most cases, she is worried her supervisors will find out about her prison time and use it as an excuse to fire her. She’s still living with her mom, though Hour Children, which runs post-release housing for incarcerated women, has offered her a spot. Merhanda doesn’t want her to take it, as it’s an hour by subway from where Merhanda lives and she won’t be allowed to stay overnight. Makeda worries it will feel like prison again, with rules and curfews.

She wonders too if prison will have long-term consequences not just for her but for her daughter. Merhanda dropped out of community college while Makeda was away, for instance, because of a $1,000 tuition bill. “I know that if I was home, that wouldn’t be the case,” she says.

“I’m still in a studio [sleeping] on the floor. I still don’t make any money. I still feel uncomfortable. I still feel ugly,” she says. “I just want something good to come out of all of this.”

Two months later, Makeda texts that she’s taken a room at Hour Children: “So far so good.” Soon after that, she texts that the nonprofit found space for Merhanda too. On a July night, Makeda jogs down from the six-bedroom apartment that she shares with three roommates (the number varies), all formerly incarcerated women, and one of their kids. The apartment building in Corona, Queens, is tidy, with well-kept shrubs, and though it’s sweltering outside, Makeda looks fresh, healthy, and happy.

She shows off the apartment, set up like a college dorm, with single bedrooms and shared common spaces and bathrooms. The apartment is dead quiet, a place where residents seem to work hard, sleep, and go to work again. Only the array of shower slides by the front door suggests that multiple women live there.

Living with women who’ve gone through what she has seems to energize Makeda. She talks about how K., who she initially met at the Rikers Island jail, brought the living room couch and how T. works construction and helps school Makeda on you’re-not-in-prison-anymore habits—like, if she uses the last garbage bag, she needs to buy more. (To protect their privacy, only the roommates’ first initials are being used.)

With her housing settled, Makeda has gotten back in touch with her dad’s family. She’s taken a second job, a night-shift gig handling auditing at a hotel. She’s watching other women who’ve done time progress as well: Two roommates are moving soon to their own places subsidized by Hour Children.

Makeda with a boy she calls her nephew. She befriended his mother, a woman with no other family, when they were in jail on Rikers Island.

Oh, and the big news: Merhanda is pregnant, due in the fall. Makeda is going to be a grandmother.

Merhanda didn’t know she was pregnant until several months in. At first, Makeda couldn’t get her head around it. Then, “I’m like, All right, I gotta figure something out. So I started looking for a second job,” she says.

She’s stocked up on onesies, thrilled about a baby coming. Still, it means a window with Merhanda is closing. “I never got to see our relationship” as just mom and daughter, she says. Once Merhanda was pregnant, “I felt like, you know, she wasn’t my Merhanda anymore.”

Makeda is eager to get a place for herself, Merhanda, and the baby, but she can’t figure out how to pay for it. She’s okay being here for a while anyway. “Where you rest your head has a tremendous effect on how you feel,” she says. “When I was in my mom’s house, I was feeling like I was in dark places. Now I feel like I can think.”

A baby carriage, a gold throne, a giant bunny, sparkling lights, balloons, a DJ: Makeda may have missed out on a lot of celebrations over the years, but for Merhanda’s baby shower she’s going all out. She’s decorated the party space in a gilded enchanted-forest theme. A crew of friends and family unpacks boxes of decorations and sets up a buffet outside. Makeda hugs everyone, adjusts flowers, and stresses about lighting and her daughter’s whereabouts. The party’s start time was six, but it’s close to eight.

“Everyone’s so late, and I’m so mad,” she says.

In the bathroom, Makeda changes into her party outfit, a dusky-rose jumpsuit, decorating her ponytail with leaves plucked from the woodland scene. Georgia, Makeda’s roommates T. and K., and more friends, family, nieces, aunts, and uncles arrive. Makeda gives orders: Do an ice run; set up a drink dispenser.

Merhanda and Makeda at the baby shower that stood in for so many missed celebrations.

At close to nine, Merhanda sweeps in, surrounded by friends. She looks luminous in glittery eye makeup, a long ponytail, and a silky white dress that hugs her weeks-from-delivery belly.

Soon, she will give birth to a baby boy named Enzo. In a video Makeda takes moments after the birth, both she and the new mom are barely able to breathe through laughter and tears. “Oh my God, oh my God,” Makeda says as Merhanda nestles the baby against her body. “Merhanda, he’s so beautiful.” It’s true: He’s a healthy black-haired little one, big for his age, with his grandma’s giant brown eyes.

Soon after Makeda’s grandson is born, her thyroid problems will get worse and she’ll take medical leave from her human-resources job, switching to a new nursing-home staffing-coordinator job. She’ll continue working sporadically at the hotel and add an hourly gig delivering medical supplies. She’ll barely make it through her term at Marymount, almost dropping one of her classes because she’s so busy, but come spring she’ll start another semester and even take a Columbia University coding class too. She’ll spend as many nights with the baby as she can, waking up to feed him and soothe him.

Ask Makeda how to improve coming home from prison and she’ll deliver a rapid-fire list: Prisoners need better nutrition so women don’t come out sick or overweight; they need wellness training and, she says, mandatory physical exercise to keep their heads clear. There should be tutorials for people about to be released with pictures—maybe videos—so they can see what the social-services office looks like or what places like Fortune can do for them. Add in field trips so inmates can understand the world they’re stepping back into. When people leave, they should get a package with essential items like T-shirts, underwear, and deodorant. Most of all, they need mentoring from people who already came home—living examples of people who got through this. In fact, that’s why she wants to code—so she can develop an app that will help people coming home have an easier time than she did.

More than a year after she gets out, sitting in her apartment, Makeda thinks back about prison. “Even though I was in that situation, it wasn’t my life,” she says. “I thought that, but I also had to get to a place where I needed to accept that it was my life and that I needed to make my life better. I felt like I cried more than any prisoner that I knew. I used to be like, What’s wrong with these people? Like, Why y’all not crying? This is really devastating.”

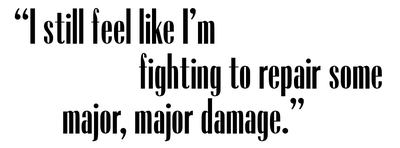

She adds, “Just to feel like one situation snatches everything from you—I still feel that way. I still feel like I’m fighting to repair some major, major damage.” Her eyes tear up, and she massages one hand with the other.

But for the moment, the party’s on, the DJ spins Ella Mai, and Makeda sings along. The room is packed, the music throbbing. Makeda and Merhanda pose for pictures. A pile of gifts gets higher and higher. An older relative fixes Makeda a plate of food, but she won’t stop to eat, doesn’t want to stay still. This is her Christmas-tree decorating, her 40th birthday, her homecoming party all in one. This is all of Merhanda’s birthday parties that she missed. This is a glimpse of a life that could have been hers—that was hers before the bar fight. She sees another Georgia who got to relax once her daughter hit adulthood; another Merhanda who grew up seeing her mom go to work every day. There’s another Makeda here too, from a place where she didn’t settle things with fights, and if she did, she didn’t get nine and a half years for it. A Makeda who still has her job, her apartment, her boyfriend, her savings, her clothes, her health—another Makeda who, at age 40, does not have to start over from scratch.

Baby Enzo with mother Merhanda and grandmother Makeda at home.

Video Produced by Rachel Lieberman / Photography Direction & Video Editing by Robert Mroczko / Sound by Andrew Salomone / Post Production by Danny Ratcliff

Stephanie Clifford is an award-winning journalist writing about criminal justice and business, and author of the bestselling novel Everybody Rise.

-

Want to Drink Like a College-Aged Prince William? That’ll Cost You £135

Want to Drink Like a College-Aged Prince William? That’ll Cost You £135Kate Middleton, for her part, liked a concoction called “Crack Baby.”

By Rachel Burchfield

-

Neither Prince Charles Nor Prince William Have Reportedly Seen an Advance Copy of Prince Harry’s Tell-All Book

Neither Prince Charles Nor Prince William Have Reportedly Seen an Advance Copy of Prince Harry’s Tell-All BookThe manuscript has reportedly been signed off on by lawyers and is due on shelves this winter.

By Rachel Burchfield

-

Melinda Gates Highlights 5 Women Inspiring Change in Their Communities

Melinda Gates Highlights 5 Women Inspiring Change in Their CommunitiesThe global advocate shares the stories of some extraordinary women whose vision and ingenuity are creating new possibilities for their countries and industries.

By Melinda French Gates

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich

-

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth

-

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.Democracy always offers a path forward even when we feel thrust into the past.

By Beth Silvers and Sarah Stewart Holland, hosts of Pantsuit Politics Podcast

-

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to Know

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to KnowThe case could threaten Roe v. Wade.

By Megan DiTrolio

-

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.Victims of sexual abuse are quietly criminalized. Sara's Law protects kids that fight back.

By Dr. Devin J. Buckley and Erin Regan

-

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water"They say that the United States is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Why are citizens still living with no access to clean water?"

By Amanda L. As Told To Rachel Epstein

-

30 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

30 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenIf anyone tries to tell you otherwise, show them these statistics.

By Megan Friedman

-

Cory Booker and Rosario Dawson's Relationship Is No More

Cory Booker and Rosario Dawson's Relationship Is No MoreAfter three years of dating, the power couple have decided they're better off as friends.

By Marie Claire Editors