Love, Hate, and Homicide in the High Desert

When a lesbian couple was murdered on a remote trail in Moab, Utah, it reinforced one gruesome truth: For the LGBTQ+ community, the great outdoors can be a deadly place. *Trigger Warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of homophobic and sexual violence.*

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Thank you for signing up to . You will receive a verification email shortly.

There was a problem. Please refresh the page and try again.

The night before Crystal Turner and Kylen Schulte went missing, five days before their bodies turned up riddled with bullets, the newlyweds chatted with friends at Woody’s Tavern in Moab, Utah, a mecca for outdoor enthusiasts that sits at the doorstep of Canyonlands and Arches National Parks. It was Friday, August 13, 2021, and Turner, 38, a petite blonde with boundless energy, and Schulte, a Cara Delevingne-lookalike with green eyes and a radiant smile, met up with friends to celebrate Schulte’s upcoming 25th birthday.

Despite being close to a foot taller than her wife, Schulte sat on Turner’s lap as they sipped ice-cold Coronas. “They couldn’t keep their hands off of each other. They were just so in love,” remembers Jessica Hannum, who was there with the couple that night. In many ways, they were opposites: Schulte worked at the Moonflower Community Cooperative, a health food store in town; Turner worked at McDonald’s. Turner was into steaks and motorcycles. Schulte was pure, laidback hippie—into butterflies, crystals, and her beloved bunny, Ruth, whom she often toted around town. “She was this bright ray of sunshine” says Joleen Oster, another friend celebrating Schulte’s birthday.

Schulte and Turner first crossed paths on the Faux Falls hiking trail, just outside of Moab, in 2016. Soon, the women found themselves working together at the La Quinta Inn & Suites. By 2019 they were a couple, and in April 2021, they married in an intimate ceremony in a treehouse in Turner’s home state of Arkansas. Both women had overcome painful pasts—drug addiction, sexual violence, the loss of close family members—and were the happiest they’d ever been together. “It was love, it was sparks. It was pure light that shined out of those two girls,” remembers Schulte’s father, Sean-Paul Schulte.

At Woody’s, the friends discussed everything from what kind of birthday cake Schulte wanted (rainbow mirror glaze) to a home outside of town the couple had considered renting. Thanks to sky-high Moab rents and a love of both the outdoors and freewheeling van life, Schulte and Turner were living in a black 1987 Econoline van, which was broken down at the moment. But with average temps in Moab hovering around 100 degrees, they were opting to camp 45 minutes from town up in the La Sal Mountains, a group of snow-capped peaks dotted with lakes and aspen trees, where the climate is much cooler.

That night, the conversation turned to a strange encounter the couple had over the previous few days. At some point that week, Schulte and Turner were lounging in a hammock at their campsite—which they described in general terms to their friends as a free spot in a dispersed area off the La Sal Loop Road close to Warner Lake—when a “creepy guy,” as Oster and Hannum remember the couple describing him, pulled up. He got out of his car and howled like a wolf at the women. The friends all laughed when Turner, a bit eccentric herself, described how she had howled right back. He got in his car and drove off.

The friends say Schulte and Turner were disappointed when he returned later with food, clothes, and blankets, and set up his camp so close to the women that it made them uneasy. “I guess he’s in it for the long haul,” Turner said to her friends at Woody’s. “If you really don't feel comfortable, you can come stay with us,” Hannum offered. She suggested that they stay in the van in the parking lot at McDonald’s. “I’ll pay the [parking] tickets if you get them,” she added. But Turner and Schulte didn’t seem all that ruffled. “He’s just some strange guy,” said Schulte in a way that seemed to indicate that the man was more of an annoyance than a threat, and the couple rebuffed their friends’ offers to stay the night. They planned on moving camp the next day. “I’ve got my eagle eye on him,” Turner joked with a smile.

The women all left Woody’s that night around 8:30 p.m. As they hugged goodbye, Schulte and Turner said with a giggle, “If we don't show up for work, come look for us.” The women never heard from Schulte or Turner again.

In a town where people rarely lock their doors, news of the double homicide rocked Moab, a tight-knit community of 5,000 year-round residents tucked into the red rock canyons of southeast Utah. But the murder of the popular lesbian couple barely made a blip on national news—bringing into sharp relief how dangerous wild spaces can be for LGBTQ+ people and how little attention the issue receives.

“The outdoors is absolutely not a safe and inclusive place for the queer community,” says Pattie Gonia, a queer environmentalist drag queen who advocates for inclusivity in the outdoors. “The outdoors as a culture is rooted in whiteness, white supremacy, cis culture, straight culture, and it’s built on making any marginalized person feel unsafe.”

Crystal Turner and Kylen Schulte on their wedding day in April 2021.

Our public lands do have a long, dark history of racism, exclusion, and violence against minorities. According to Kaejang Lee, professor of parks, recreation, and tourism at North Carolina State, national parks were created by white elites who had “imperialistic, xenophobic, and racist views.” This lack of diversity has continued to the present day and is echoed in the outdoor sports industry, which—as a look at most industry magazines or marketing materials will illustrate—is predominantly white, hetero, and cisgendered.

So, it’s no surprise then that the LGBTQ+ community doesn’t feel welcome, or at times, even safe in the outdoors. “Homophobic violence in the outdoors, racist violence in the outdoors is happening all the time,” says Jenny Bruso, an LGBTQ+ advocate and founder of Unlikely Hikers, a community creating experiences for underrepresented people in nature. “I feel more on guard in the wilderness than I do in daily life. I’m aware of the lack of people around and the possibility of something terrible happening,” she adds.

When violence in the outdoors against underrepresented communities does happen, it often goes unnoticed. Shortly after Schulte and Turner were murdered, another vanlifer disappeared. In early September, Gabby Petito, an attractive 22-year-old blonde, vanished. A few weeks earlier, the Moab City Police had interceded in a fight between Petito and her boyfriend, Brian Laundrie, 23. A nationwide manhunt and media storm ensued, with coverage on CNN, 48 Hours, Fox News, and others. Thanks to the publicity, Petito’s body was found on September 19 in Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park. (Laundrie’s body was discovered a month later in Florida. He’d died by suicide.) The disparity in national interest between the two cases is jarring. “Just look at the level of coverage [Gabby Petito’s case] has gotten versus ours—two lesbian hippie chicks—and what indigenous women get, which is none,” says Sean-Paul.

Far from an anomaly, Schulte and Turner’s case shares similarities with several high-profile murders of gay couples in wild places. In 1988, Claudia Brenner, 31, and Rebecca Wight, 28, were making love by a stream on a section of the Appalachian Trail in Pennsylvania when Stephen Roy Carr, a 21-year-old ex-convict they’d come upon earlier in the day, fired eight shots at them, killing Wight and severely injuring Brenner. At the subsequent trial, the defense argued that the women’s sexual orientation and lovemaking had provoked Carr, igniting in him an “inexplicable rage.” In May 1996, the young couple Lollie Winans, 26, and Julie Williams, 24, were found bound and gagged with their throats slit in Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park. And in June 2012, Mollie Olgin, 19, and Kristene Chapa, 18, were sexually assaulted and shot execution style at Violet Andrews Park in Texas. Olgin died, but Chapa miraculously survived. Four years later, David Strickland was convicted of the crimes. One of the key pieces of evidence against him was a 2014 letter sent to Chapa’s father that read, “Fucking lesbians, they are less than people and I wanted them to know that.”

Intimidation, exclusion, assault—there are countless more examples of aggression against the LGBTQ+ community in our parks and campsites. In 2020, on the first day of queer, professional adventurer Mikah Meyer’s run across Minnesota, an effort to raise awareness about diversity in the outdoors, a passenger in a moving vehicle screamed “Faggot!” at him. Gonia, the environmentalist drag queen, says they have faced overt homophobic comments, even death threats. The National Park Service reports 14 hate crimes since 2016, but the real number is likely much higher because hate crimes, in particular those against homosexuals, are notoriously underreported, according to Frank S. Pezzella, an associate professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Emerald LaFortune, a queer whitewater and fishing guide in rural Idaho, hesitates to be forthcoming about her sexual orientation in wild spaces. “I wish I could put that Progress Pride Flag on the bumper of our F-150. I want other queer folks to know they aren't alone out there,” she says. “But when I pull off on some dirt road in middle-of-nowhere Idaho to camp for the night, the risk, especially as a queer woman, just isn't worth it.”

Turner didn’t show up for work on Sunday, August 15. When there was no sign of her again Monday, one of Turner’s managers reported her missing to the police. Schulte also missed her shift at Moonflower. Desperate to find his daughter and her wife, Sean-Paul posted an imploring message on Facebook on Tuesday, August 17: “Moab peeps…Kylen and Crystal are missing….please help look for my girls.”

Cindy Sue Hunter, 64, who first met Kylen and Sean-Paul in 2016 when they visited her Moab art gallery and craft store, was among a handful of friends who took up the cause. On Wednesday morning at about 7 a.m., she got in her car and headed towards the La Sals.

No one knew exactly where to look; the location the couple had told their friends about at Woody’s was vague and the La Sals are vast. The police had already searched Warner Lake and its environs. So, for four hours, Hunter drove around the mountains, looking for any trace of the young lovers. Around 11 a.m., Hunter, a believer in the supernatural, asked Schulte and Turner to guide her to them. She says she then began to hear their voices directing her to the South Mesa section of the La Sals. Hurry, hurry, they said. Soon after, a flash of silver caught her eye. She stopped her car, backed up, and saw a campsite. She followed a hidden dirt road down to it, where she came upon Turner and Schulte’s blue Kia Sorento.

Hunter got out of her car and began to poke around the camp. It was monsoon season, and rain had soaked the ground the night before. The sky hinted at an impending storm and Hunter’s three dogs barked incessantly. The campsite was in disarray. “It wasn’t ransacked, but it just didn’t look or feel right,” Hunter recalls. She came upon Schulte’s rabbit in a makeshift enclosure, and the bunny was out of food and water. She got in her car and called the police. Then she phoned Sean-Paul.

“Do you see the girls?” he asked.

She didn’t, so she decided to walk around a bit more. Sports drink bottles were scattered about, clothes were under a tree, and their tent, askew with its door open, revealed a cell phone propped up inside. Hunter was walking towards the irrigation ditch that hemmed in the campsite when she spotted a partially submerged body, its limbs at awkward angles. It was Schulte. (Turner was later discovered by authorities in the same ditch, but further from the camp.) Hunter instantly went into a state of shock, turned away, and started babbling incoherently to Sean-Paul. She looked back to make sure of what she’d seen; it was then she began to scream.

On August 19, 2021, the Grand County Sheriff’s Office issued a press release officially identifying Turner and Schulte as the victims, asking the public for information, and stating that it believed “there is no current danger to the public in the Grand County area.” Shortly after, the Grand County Sheriff brought in the FBI and Utah’s State Bureau of Investigation.

The Sheriff’s Office put out a warrant on September 20 for Verizon, asking for all cell phone records from August 13 to 15 within a two-mile radius of the tower nearest the couple’s campsite. The warrant describes a gruesome crime scene: Both women were found in the creek, “undressed from the waist down, one had on a bra that was raised to expose her breasts, the other was dressed only in a tank top.” Each woman had been shot multiple times in the sides, back, and/or chest, and four silver 9mm bullet casings were found nearby. The warrant seeks evidence for the crimes “of Murder, conspiracy to commit murder, tampering with evidence, sexual assault, desecration of a corpse, rape.”

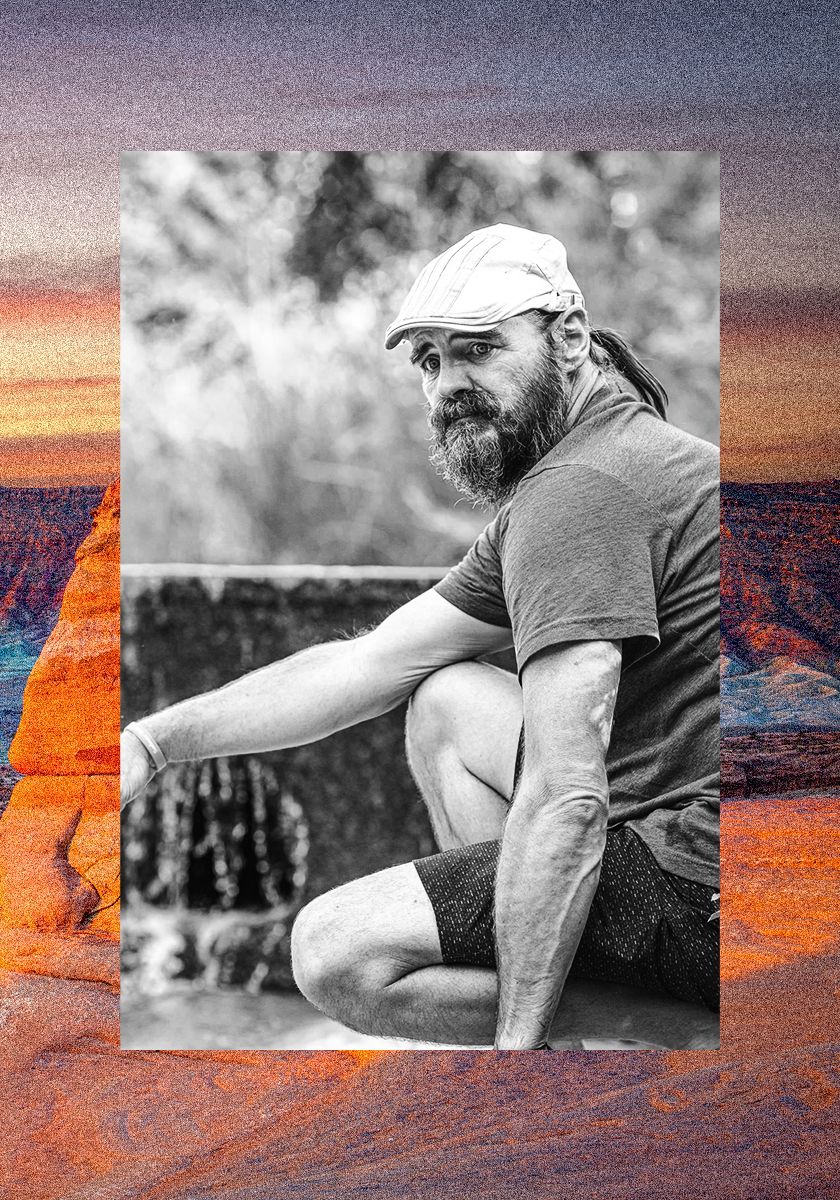

Desperate to find justice, Sean-Paul decamped to Utah in early September to set up what he called a clue booth in Moab’s Swanny City Park, an airy green in the town center. Almost every day for five weeks, Sean-Paul, his blue eyes wild with grief, sat at a table under a small shelter adorned with photos of the girls, notecards, and a box for anonymous clues. His hope, he says, was to collect leads from people who might not want to go to the cops. By the time he left town in mid-October, he’d received close to 50 credible tips, which he handed over to the authorities.

In October, Jason Jensen, a private investigator and cofounder of the Utah Cold Case Coalition, volunteered his services to Sean-Paul. Together, they chased down the clue booth leads and came up with a shortlist of suspects. Despite the lack of available evidence, Jensen was able to discern one incontrovertible fact: the crime had been extremely violent. “It appears the gun was emptied on them, which indicates deep anger, a lot of hate,” says Jensen, who notes that both women were shot six times. “A hate crime is definitely a motive that’s on the table.”

Sean-Paul Schulte, Kylen's father, moved to Moab and set up a clue booth to help solve the murder of his daughter and her wife.

From August to May, little information was made available to the public, and until the case is adjudicated most of the records are sealed. But for seven months, Jensen and Sean-Paul pursued their own investigation. As a means to crowd source leads and keep the case alive, family members and friends launched the Facebook page “Remembering Kylen Schulte and Crystal Turner,” which by May 2022 had more than 10,000 members. At times, Sean Paul and the group’s amateur sleuths, who called themselves the KyCry Warriors, felt frustrated by the authorities’ seeming lack of progress on the case and they, along with outside observers, couldn’t help but wonder if it had to do with the women’s sexual orientation. “I think the lack of progress absolutely had to do with them being queer,” Bruso, the inclusivity in the outdoors advocate, says.

In early May, just in time for prime tourist season, Sean-Paul, in the spirit of Frances McDormand in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, rented a sign on private land alongside Highway 191 at the southern entrance to Moab. “Who Killed Kylen and Crystal?” is splashed in yellow letters above a giant photo of the women, their radiant smiles beaming hauntingly from the 28-foot billboard, which, if entering the town from the south, is unmissable. It also includes a call for more leads, contact info for the Grand County Sheriff and Jensen, and a reward for $20,000.

Then on May 8, Dog the Bounty Hunter, the mullet-sporting TV personality and sleuthhound who Sean-Paul had begged for months to take up the case, arrived in Moab with a 10-person crime-solving crew. Two days later, Dog, who claims to have captured more than 10,000 fugitives, held a press conference. “The murderer had to know them,” Dog said confidently. He added that he believed the perpetrator was likely someone who worked in Moab and that the crime was one of love or hate. Dog and his team spent a week canvassing Moab, penetrating its seedy underbelly and running down leads. To date, they’ve generated at least 1,000 tips, which they continue to pursue.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the day after Dog’s press conference, the Grand County Sheriff’s Office held its own. On May 11, Sheriff Steven White stepped up to a microphone and announced that they’d finally identified a suspect: Adam Pinkusiewicz, a drifter and former coworker of Turner’s with a criminal record and a history of mental illness and homophobia. The authorities were able to place him in the La Sals at the time of the murders and said that he’d left the state quickly. Shortly thereafter, he died by suicide. Prior to his death, he’d confessed to another party, “that he had killed two women in Utah and provided specific details that were known only to investigators,” according to Sheriff White.

Pinkusiewicz had long been on Sean-Paul’s shortlist: Early on at the clue booth, Sean-Paul had heard that Pinkusiewicz had gotten into scuffle with Turner when she came into the McDonald’s kitchen off-shift to make some food for herself and Schulte. “Why are you back here? You don’t have the right to be back here!” he belligerently screamed at Turner. At the time, Merry Woodruff, a manager at McDonald’s who witnessed the episode, thought it was odd that he was so upset. In hindsight, she thinks it was his homophobia rearing its ugly head. On August 7, Woodruff recalls, Pinkusiewicz got into a rage-filled argument with another lesbian coworker in which he used homophobic slurs and threatened violence. “You want to act like a man? You want to be a man? I’ll show you how a man is. I’ll take you out back and beat you up,” Woodruff remembers him screaming at the coworker. Fearing for her safety, the coworker left McDonald’s that night. Less than a week later, Schulte and Turner disappeared. Pinkusiewicz never returned to work, not even to collect his last paycheck.

But Dog the Bounty Hunter isn’t convinced Pinkusiewicz is the murderer. “I’m skeptical that the Sheriff has the right guy,” he said in late May. While on the ground in Moab, Dog heard that Pinkusiewicz was openly gay, which throws the homophobic hate crime motive into question. On top of that, his team has been unable to find Pinkusiewicz’s death certificate in various record searches. And what about the “creepy guy” who had prowled around their campsite? Sean-Paul thinks it was probably Pinkusiewicz, but wouldn’t Turner have recognized a coworker; why would she not have ID’d him to her friends at Woody’s? Finally, there’s the fact that three weeks before the sheriff’s press conference, authorities showed up at the home of Cindy Sue Hunter, the friend who had discovered the women’s bodies, asking her to turn over her cell phone and telling her that she was now a suspect. “It all just doesn’t add up,” says Dog. [Editor's Note: We have asked the police to confirm whether Cindy Sue Hunter remains a suspect, but no response was received as of publication date.]

Without a suspect that’s alive, no one can know for certain if the murder of these Moab wives was a hate crime. But the truth is even if Pinkusiewicz was alive, or there was another credible suspect still under investigation, bias motivation is often hard to prove. Pezzella, the professor of criminal justice, says that in the absence of a confession, a symbol, or a report of hateful language, the likelihood of proving the murders were a hate crime is low.

Given the brutality of crimes that have occurred in the wilderness to the queer community, it’s no wonder that LGBTQ+ recreationalists take safety into their own hands. Bruso always carries spray and a knife when hiking. Gonia suggests traveling in numbers and in highly trafficked areas and always having a satellite beacon. “But this shouldn’t just be on the individual—there needs to be systemic change,” says Gonia. “We need for the systems and powers that be to show up more as well.” Ultimately, they would like to see a more diverse outdoor recreation culture, one that is truly allied with marginalized communities. “This looks like stomping out homophobia on the trails whenever we hear it, being alert for signs of people who might be in danger or at risk, diversifying our outdoor groups and organizations, and supporting organizations that get systematically-excluded youth outdoors so that we can further diversify the trails,” they say.

Sean-Paul is still waiting for the Grand County Sheriff’s Office to come out with evidence—ballistics, DNA—that conclusively links Pinkusiewicz to the crime, but he believes Pinkusiewicz is likely the murderer. (As of press time, no further updates on the case have been released.) In the meantime, he has begun to transform his tragedy into a force for good. “Divine intervention has dropped my life’s work into my lap,” he says. In May, he established the SunnyRose Housing Foundation in honor of Schulte and Turner. The organization takes its name from the women’s respective favorite flowers, a sunflower and a rose, and will provide housing for full-time, low-income workers in Moab. “I believe that if the girls were safely locked in a home, if it was harder for him to access Kylen and Crystal,” Sean-Paul says, breaking into sobs, “my girls still might be here.”

For nine months, Sean-Paul had a recurring dream in which Turner, wearing her trademark beanie, appeared to him, often whispering, “Come on, Dad, you’re close.” He took that as a sign that he was on the killer’s trail. Turner’s words of encouragement soothed him and fueled his search for the murderer during the long months when it seemed the case might never be solved. But seeing Turner in his dreams also amplified his despair. He longed to see Kylen one last time and feel the sunshine of her spirit, even in the hinterland of the unconscious. Then one night shortly after the sheriff announced that Pinkusiewicz was a suspect, the dream changed. For the first time, Kylen appeared, as beautiful as ever. Crystal was to her right, smiling. A sense of love and peace emanated from them.

Kelley Manley is a freelance journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Vogue, Marie Claire, Departures, and other national and regional publications. Follow her on Instagram @KelleyMcMillanManley.

-

How This Royal Lived Incognito for 13 Years

How This Royal Lived Incognito for 13 YearsThis is kinda crazy.

By Iris Goldsztajn

-

Prince Harry May Well Come Back to the U.K. "In a New Role" When Charles Is King, His Former Protection Officer Says

Prince Harry May Well Come Back to the U.K. "In a New Role" When Charles Is King, His Former Protection Officer SaysCould you see this happening?

By Iris Goldsztajn

-

Princess Anne Has a Pretty Unusual Food Preference, According to a Former Royal Footman

Princess Anne Has a Pretty Unusual Food Preference, According to a Former Royal FootmanSome might even call it...bananas.

By Iris Goldsztajn